By Li Qi

The Great Game is a cruel one. This famous yet frivolous term originally referred to the nineteenth-century military and diplomatic rivalry between the British and Russian empires for hegemony over Central Asia—an imperial contest that left the region in turmoil and decline. In recent years, the phrase has been repurposed to describe other playgrounds of empires, from the struggle among Russia, China, and Japan for dominance over the Korean Peninsula in Sheila Miyoshi Jager’s latest book The Other Great Game: The Opening of Korea and the Birth of Modern East Asia (2023), to the US and USSR’s polarizing influence over Southeast Asia during the Cold War. The latter formed the historical backdrop of “The Shattered Worlds: Micro Narratives from the Ho Chi Minh Trail to the Great Steppe,” an ambitious exhibition co-organized by the Jim Thompson Art Center and the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre in Thailand, and curated by the Art Center’s artistic director, Gridthiya Gaweewong, and her team. The exhibition revisited the struggles of smaller nations caught in the clashes of superpowers, and the unresolved issues left by the opposing ideological blocs. It ultimately held a mirror to the present, with countries along the Indochinese Peninsula and the South China Sea once again being pulled into opposing spheres as a new contest unfolds across the Indo-Pacific.

The exhibition brought together thirteen artists and collectives from Southeast Asia, neighboring nations, and as far afield as the Eurasian Steppe. It was anchored by two expansive research-based projects, both presented at the Jim Thompson Art Center, to reexamine the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), a mid-twentieth-century transnational political effort aimed at resisting alignment with either the US or the USSR. Two Meetings and a Funeral, 2017, a three-channel film by Bangladeshi British artist and academic Naeem Mohaiemen, revisits the ill-fated attempt to unify the Third World, which was ultimately undermined in the 1970s by ideological rifts between NAM and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation. A roundabout: Blooming mementos, towards monument, 2025, a mini showcase by the Indonesian collective Hyphen—, investigates the myth, symbolism, and political gesture of the 1955 Asian-African Conference in Bandung, Indonesia. While both projects draw on archival footage and historical imagery that once celebrated South–South solidarity, they are tempered by a skeptical tone. NAM is treated as a utopian precedent whose viability for today’s Global South remains uncertain.

The larger portion of the exhibition unfolded at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, where the artists surveyed both visible and invisible residues of Cold War power plays. In the short documentary film Vision in Darkness (2015), late Vietnam-born artist Dinh Q. Lê retraces the transformation of modern Vietnamese master Trân Trung Tín (1933–2008), who moved from producing state-sanctioned works to pursuing freer expression in painting. Chinese Austrian artist Jun Yang turns his gaze on the space race with a mirrored monolith accompanied by neon light and photographic archives, while Kazakh artist Almagul Menlibayeva investigates the nuclear-arms race through a five-channel video installation that reveals a secretive desert town. Malaysian artist Au Sow Yee, meanwhile, attempts to recollect lost tales and memories from the sea through semifictional stories in her video installations.

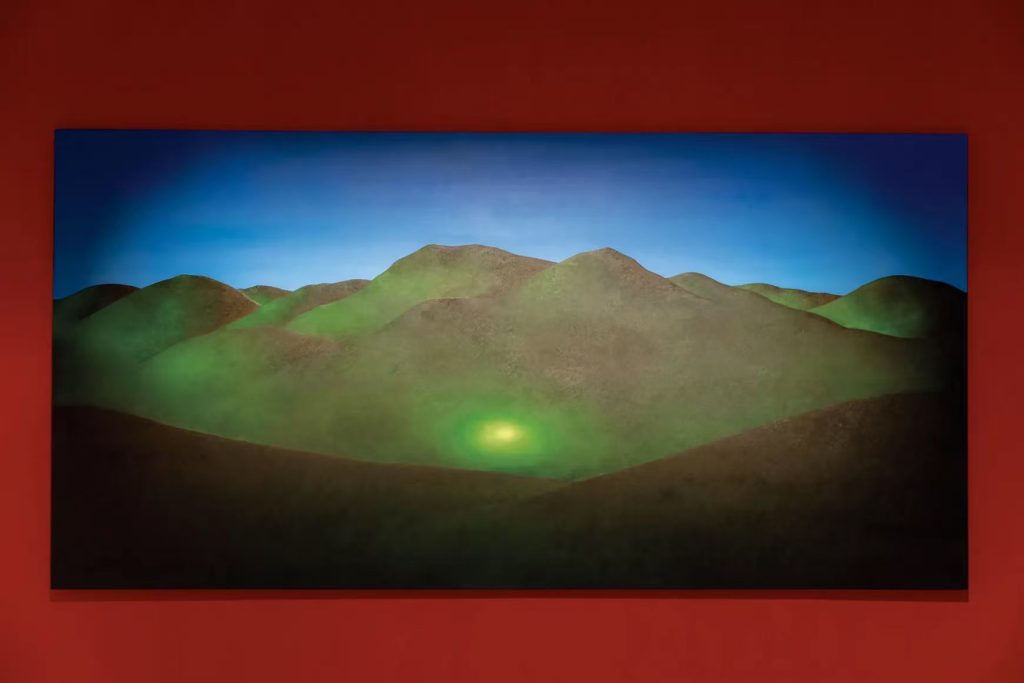

Thai artists focus on more localized topics regarding the Cold War’s aftermath. Vacharanont Sinvaravatn paints eerie landscapes of Thailand’s once violence-ridden southern “red zones”; Chulayarnnon Siriphol, in his Red Eagle Sangmorakot project, 2024, reenacts for the camera the entanglement of Thai boxing, masculinity, and national identity; Som Supaparinya juxtaposes Cold War–era signage found in Thailand and Laos with photographic records of diplomatic meetings from 1961, highlighting the stark divides across adjacent borders.

As if testing history against present reality, this politically charged exhibition arrived amid the simmering border dispute between Thailand and Cambodia, with no works by Cambodian artists on view. Despite this shortcoming, “The Shattered Worlds” managed to remain poetic and imaginative, with one eye turned toward the past, the other toward the future—reflecting the desire to consolidate Southeast Asia’s global position and chart a new, and hopefully peaceful, path forward.

Published on ARTFORUM, October 2025, Vol. 64, No. 2. Read the original on artforum.com.